On the evening of February 5th, the Lincolns had shuttled between his upstairs sickbed and the East Room. The boy had been seriously ill, probably from typhoid fever, for more than two weeks. Amid a clamor of national pride, the President quietly observed, “I have just been watching your father and mother on television, and they seemed very happy.” A hundred years earlier, almost to the hour, the set of parents then occupying the White House, Abraham and Mary Lincoln, were being plunged into an extreme grief by the death of their third son, Willie, who was eleven years old. Kennedy was on the phone congratulating John Glenn, who had just completed three orbits of Earth.

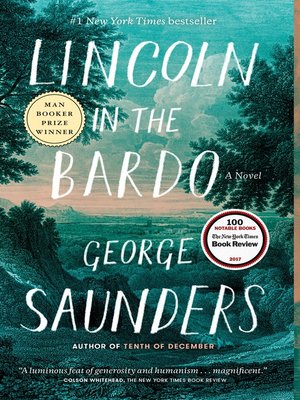

Another eerie conjunction belongs to February 20th, which delivered to the White House, on two occurrences a century apart, some of the keenest joy and deepest sorrow to enter the building.Īt 4:10 P. Seekers of Presidential frisson cherish the synchronous deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, on July 4, 1826, a temporal thrill doubled by the date’s being the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Among the graveyard’s permanent guests - a teeming mass that includes a stern, eloquent reverend, a dreamy young man driven to suicide by a lover’s rejection, a perpetually sloshed married couple, and a dandyish trio of top-hatted bachelors - only one receives a regular visitor: Little Willie, whose devastated father returns to his crypt nightly to hold the boy in his arms, even as he struggles to accept that “the essential thing (that which was borne, that which we loved) is gone.Saunders, in his début novel, boldly enters the psyche of our sixteenth President. Dozens of souls trapped somewhere between this mortal coil and whatever lies on the other side, they’re dearly (and often messily) departed but don’t know it, emerging from the coffins they call “sickboxes” to fret and wander and obsessively recount the unfinished business left behind. While Bardo (a Tibetan term for the liminal state between life and death) bears Abraham Lincoln’s name and is inspired by a lesser-known episode in his life - the loss of 11-year-old Willie, his youngest and most beloved child, to typhoid - it uses him mostly as a supporting player, a living link to the vast cast of characters that populate the cemetery in which nearly all of the narrative is set.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)